When the great illustrator Howard Pyle died in 1911, his heartbroken disciples gathered in his studio. Pyle had been a phenomenal creative force, the illustrator of over 125 books (24 of which he had written himself) and hundreds of stories in the most popular magazines of his day. Vivid images of pirates, knights, soldiers and lovers flowed from his boundless imagination.

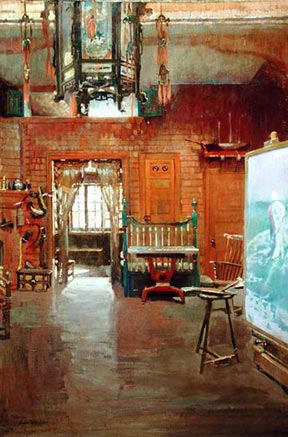

Pyle’s students struggled for some way to prolong their master’s presence. One of his students, Ethel Leach, painted Pyle’s studio exactly as he left it, with his last painting unfinished on his easel.

Another student, Frank Schoonover, took that final painting and attempted to put some finishing touches on it.

Other students went on to imitate Pyle’s techniques or used the same paints. But he was gone, and nothing they did could extend Pyle’s magic. Pyle had done his best to pass along his artistic secrets to his students, yet no one could say where his great gift first came from or where it resided during his lifetime. And now, no one could extend its stay on earth.

Other students went on to imitate Pyle’s techniques or used the same paints. But he was gone, and nothing they did could extend Pyle’s magic. Pyle had done his best to pass along his artistic secrets to his students, yet no one could say where his great gift first came from or where it resided during his lifetime. And now, no one could extend its stay on earth.

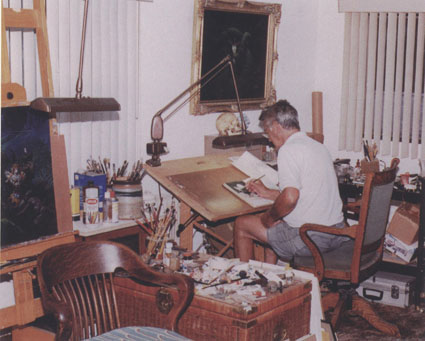

Comic artist Jack Kirby sat at this ratty, stained drawing board next to this crummy, battered credenza, stared at this brick wall and summoned up thousands of images of Norse gods in ornate armor, intergalactic empires swarming with alien creatures, super heroes and and cosmic villains.

The legends he composed on this well-worn piece of lumber caught the fancy of millions. Then Kirby was gone. Deprived of Kirby’s spark, his studio now seems so sodden and inert that we are amazed such an environment could ever have been the platform for all that creativity. Whatever the source of Kirby’s greatness, it wasn’t to be found amongst the tools and furniture he left behind.

Like Pyle or Kirby, Bernie Fuchs was another radiant star orbited by epigones and myrmidons over his long career. Fuchs too kept coming up with fresh and beautiful ideas that none of his imitators could match, despite their long hours spent trying to master his secrets. If they had gone to his cluttered studio on the day he died and looked for clues in what he left behind, they would be no closer to understanding his magic ingredient.

Like Pyle or Kirby, Bernie Fuchs was another radiant star orbited by epigones and myrmidons over his long career. Fuchs too kept coming up with fresh and beautiful ideas that none of his imitators could match, despite their long hours spent trying to master his secrets. If they had gone to his cluttered studio on the day he died and looked for clues in what he left behind, they would be no closer to understanding his magic ingredient.

The empty studio, now devoid of its creative presence, has a particularly hollow sound.

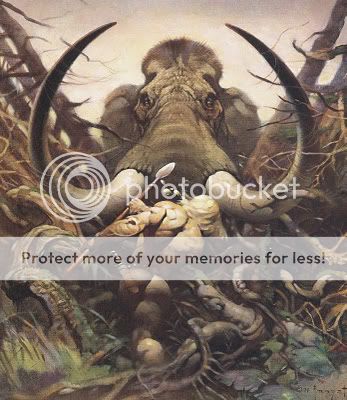

Yesterday, the great Frank Frazetta passed away. Over a long career he used his artistic talents to create persuasive worlds of sorcerers and barbarians—fantasy worlds where the four points on the compass were heroism, strength, adventure and great asses on women. What could possibly be better than that?

Frazetta’s hundreds of imitators wished they could inhabit that world, but their colors were somehow never quite as perfect, their reptilian creatures were never quite as convincing, their compositions were never quite as dramatic, their poses were never quite as striking.

If you look for the special magic ingredient that distinguishes Frazetta from his peers, you won’t find any clues left behind in his studio.

Objectively speaking, artwork like Frazetta’s should be created in a cave with flaming torches and skulls. Instead, it was created in a messy room by a grandfather wearing short-sleeved polyester shirts over his paunch, an artist who spilled coffee on his work as he raced to make deadlines. Frazetta’s studio, like the studios of other great creators before him, was a place where a temporary and unexplainable breach in the laws of physics permitted true alchemy to occur. With the creative presence extinguished, the laws of physics close in once again, and weigh on us more heavily in that spot than they did before.

David Apatoff likes great pictures and writes about them on Illustration Art.

beautifully written. thank you.

Sad thing is is that his studio has been empty for some time now thanks to the thieving children and that pirate Pistella…I don’t think a single tube of paint has been there in months.

Beautiful post, just beautiful. Looking forward to more.

The world is a much more dreary place now that he’s gone. Thank you for writing and posting this.

The hollow feeling we all have in our hearts is beautifully described by your article, David. Thank you for this. The wonder created by these great masters does endure in the works left behind, but it is the anticipation for the next work which saddens us, and the ache never quite fades away. We know it is over, but we linger at the door for one last glimpse, one final hope.

Thanks for starting an insightful post about artists and their work environment and ruining it with a reminder that women aren’t really people, just tits and asses for your delectation. Presumably Ethel Leach also had a “great ass” or you wouldn’t have bothered mentioning her.

The rampant sexism in the Tor blog posts of late has been really alienating, and makes me pretty unlikely to support the company with my dollar. There’s better stuff out there produced by companies who don’t endorse oppressive behavior.

Laughingrat, I don’t know if you have ever seen any of Mr. Frazetta’s art, but it would be hard to spend more than 10 minutes looking at it before realizing that he had a thing about “great asses.” Frazetta himself commented on it and people have laughed about it for years.

Perhaps we should avert our eyes from Frazetta’s “oppressive behavior” but I think it would be far better to simply destroy his paintings that focus on asses. You are right, it’s time somebody took a stand!

David: I didn’t know Schoonover “finished” Pyle’s painting….that takes more guts than anyone should have. Which is not a compliment.

Laughingrat: It is difficult to see how this post is sexist or that it makes tor.com sexist by extension. By my reading, David holds Leach’s tribute to Pyle in greater regard than Schoonover’s.

Although it _is_ true David was remiss in not pointing out that Frazetta was equally gifted at male-behinds:

[IMG [/IMG]

[/IMG]

This was great, Irene. Thanks.

Now I also know what to paint if someone asks me to do a great male behind too!

Craig Elliott Gallery

As to his figure work: Frazetta distorted the figure, ALL figures, to bring out the drama he wanted to drive. He was able to do that by going beyond the classical and present a feeling from the paint that goes beyond the visual surface.

An artist gets that through distortion, whether it’s technical, visual, or conceptual. To not see that is understandable because it’s a difficult thing to master, and display, and the viewer also has to ‘work’ at seeing into it. (the brain enjoys this kind of work, btw.) The best artists can drive that home, and not only get away with it by breaking ‘rules’, but they do it so well, it feels natural to the viewer.

THIS is what made Frazetta so powerful. It was his ease at presenting the guts of his thoughts. He mostly painted nude figures. He liked nudes. He loved THE BODY. This much is clear, just by looking and studying.

To think that this somehow represents a statement about sexism is to miss the point entirely.

David! What an excellent and insightful post on Frazetta’s passing! Brilliant. I am fascinated by other artists’ studios. I am always struck by how humble these studios are of such powerful painters. My own studio is not interesting and hasn’t been for most of my career. It just doesn’t matter how grand the environment, it’s what’s coming off the board.

Your post brought that home so well. You found such an inspiring point of view of Frank’s passing. Thanks! I hope I can imbue my own studio with such energy!

Just a couple of things of note:

Frank didn’t have a paunch when he was meeting deadlines. He was a big smoker, and outdoor junkie and a guy who met deadlines only when they were looming. He’s the classic work-better-under-pressure guy. Ellie and Frank both attested this to me personally, repeatedly. I’ll take their word on it because I know people like this, who work better under pressure and are big time procrastinators.

He got the paunch when his health was failing during his long struggle his thyroid disease. His days of being a physical dynamo ended then and hope of getting it back when he finally felt better was cut short by the strokes. He looked real good when I saw him last in ’95.

As a granpa he was not meeting any deadlines. He was pretty much retired doing the occasional job for very high pay.

Gregory Manchess is on the button too. Frank’s ability to balance reality with exaggeration was his true gift. And if it was easy to do he’d have a had a lot more competition from those who tried and failed miserably to imitate what Frank had almost innately.

Another thing not given enough attention was the man’s incredible ink pen and brush drawings, for a lot of us, this is the cream of Frank’s efforts. His E.R. Burroughs illustrations to his portfolio releases like Women of the Ages are without comparison.

Gregory’s remarkably talented too! I’m currently waiting for the arrival of my copy of the Wandering Star edition of the third volume of Robert Howard’s Conan. Gregory illustrated this edition and the work is remarkable.

Frank’s heirs in talent and his fans are a lucky lot. We all grew up scanning book racks at neighborhood book nooks waiting for the next paperback cover or Warren magazine cover masterpiece. I found my first one in a 7-11!

We’re carrying those harrowing, sexually charged flights of fantasy horror to our graves.

I could not thank Frank enough for that!

Now I’m off to pay attention to the tunes by Frazetta’s fave. The Chairman calls.

Laughingrat: In the Frazetta book, “Legacy,” he says: “I could probably sit around and paint fannies all day… Talk about simple shapes! It’s so dumb. Two very simplistic curves, but fascinating as hell.”

Apparently you don’t find them quite as fascinating, but nevertheless it would be a mistake to conclude that Frazetta or his fans believe “women aren’t really people, just tits and asses for your delectation.” In fact, anyone with a passing famliarity with the Frazettas’ long and devoted marriage would laugh at your conclusion. Frank was fearless in most respects, but as far as I know he never had the nerve to cross Ellie (who was apparently tougher and smarter than he was). He was dependent on her, and he knew it. They were as married as two people can get.

Irene: I had the same reaction about Schoonover “touching up” Pyle’s last painting. He added a jumping fish, a crab, and sharpened the focus around the feet of the fisherman. Personally, I think he just wanted to be part of something that the master had done, but his rationale was that the painting would be harder to sell in the state that Pyle left it.

Greg: Thanks very much for your kind words. I enjoyed your own thoughts on Frazetta. If the artists I have cited are any guide, the more commonplace and shabby your studio, the greater you will be.

Rick Tucker: thanks for your thoughts. I agree with what you’ve said. There are many legendary (and funny) stories about Frazetta doing his best work at “the last minute.” I hope someone writes a biography of the man.

Schoonover did WHAT?!

Thanks so much for this great post and a look at the studios of such legends. Wow, were they ascetic! Artists often like to be surrounded by stuff to feed their creativity. These guys knew how to shut out the distractions and turn inward to that place- somewhere between sleeping and waking- where the magic happens.

Mr. Apatoff’s “four points on the compass” made me laugh. Am I sexist (a traitor to my kind)? I’d rather think I’ve learned to look past the asses and understand Frazetta’s fascination with form and expression- of male AND female parts. Though I gotta admit, no matter how many “scifi geek” properties get embraced by the mainstream, that’s one of those iconic things us fantasy fans find hard to defend when cornered. (“Reubens did it, too.” “Yeah, but he’s not van art.”)

While I agree, that the way Frazetta painted the female form can’t be used to classify his paintings as sexist, for the very reasons you guys already stated, I do have to acknowledge, that there are a couple of questionable situations depicted, which don’t exactly seem to promote the idea of equality.

Flash for freedom, anyone???

The last few days I’v been taking a careful look at the pictures at frankfrazetta.org. I have seen powerful man. I have seen powerful woman -sometimes even in the same picture. But while I have seen numerous man save woman, I have yet to see a woman rescue a man.

(Although cornerd goes somewhat in that direction.)

But then again i’m only at page four.